How did cemeteries agree to provide everlasting care in an ever-changing landscape?

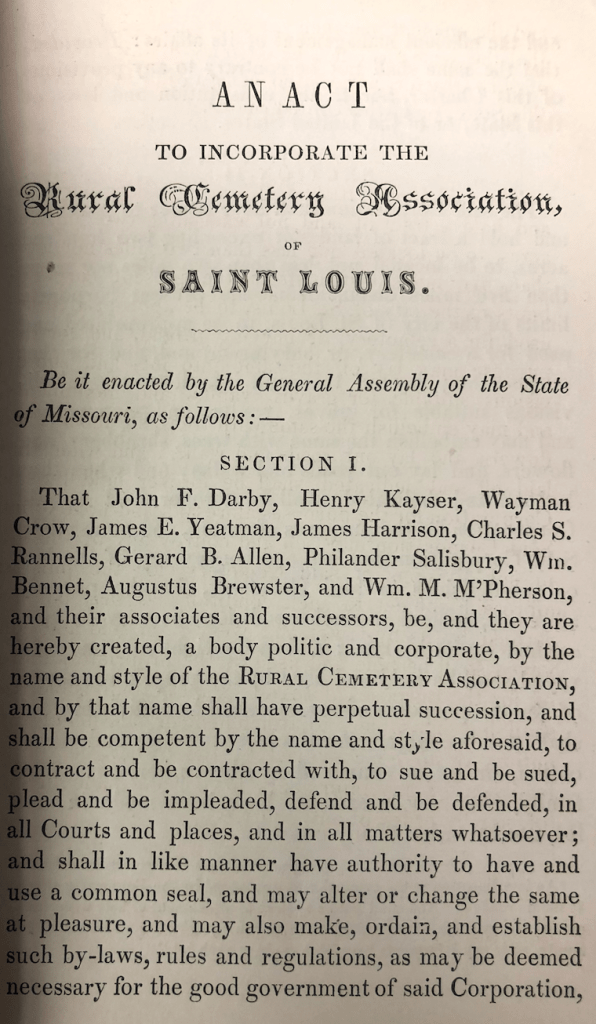

hen Bellefontaine Cemetery opened in 1849, St. Louis had already seen a chaotic pattern of cemeteries opening, closing, and being relocated. City expansion and waves of cholera filled burial grounds faster than they could be maintained. Amid this instability, Bellefontaine stood apart by making a bold legal promise: in the first section of its 1850 Charter and By-Laws, the cemetery declared it would “have perpetual succession.”

As a result, of this chaotic history, Bellefontaine Cemetery established in the first section of its charter and by-laws that they “shall have perpetual succession…”(1850 Charter and By-Laws). This enabled them to provide perpetual or extended care, a reasonably new concept at this time.

This early embrace of perpetual or extended care was a relatively new concept at the time. It meant that Bellefontaine committed to caring for its grounds indefinitely, adapting to new conditions as the city evolved. This wasn’t just legal language—it reflected a structure built for sustainability.

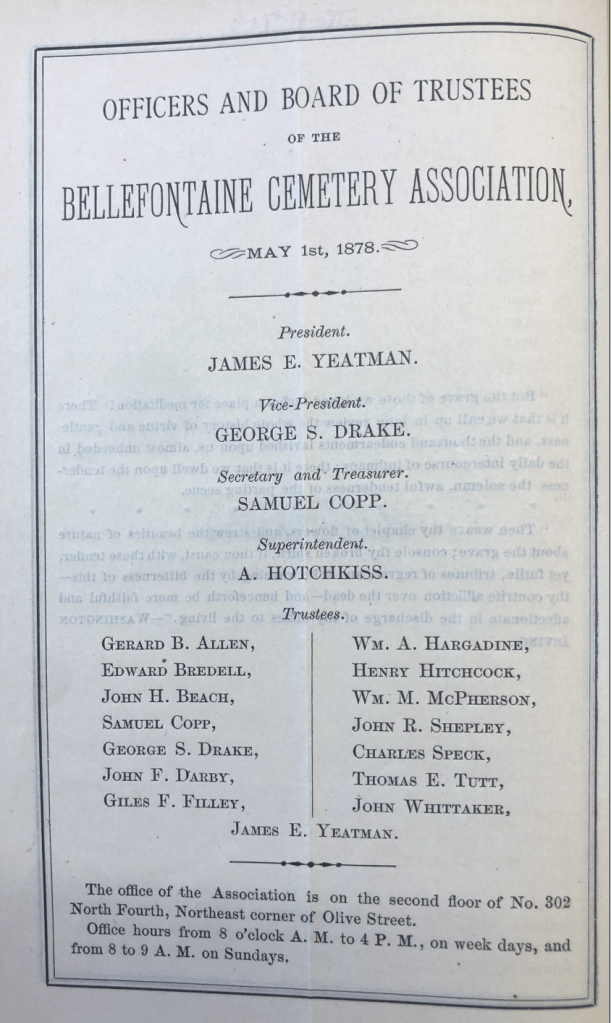

Furthermore, the Bellefontaine Cemetery Board of Trustees are elected by lot holders. To be considered for election, one must be a lot holder themself.

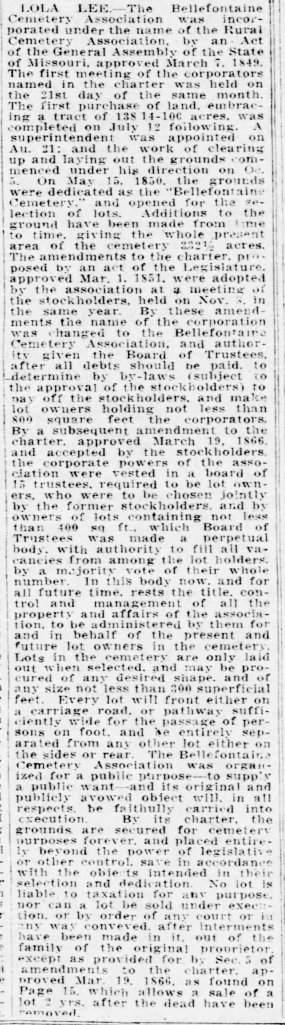

A historical newspaper clipping in my research shows how lot holders were regularly invited to participate in board elections, reinforcing transparency and accountability. It is an example of an announcement that would have been sent out to all lot holders informing them of an upcoming vote.

Having a Board of Trustees that is invested in the cemetery and, ultimately, its long-term success enabled the Bellefontaine Cemetery Association to adapt and make changes to common issues quickly.

The earliest list of Bellefontaine trustees published in 1878 by the cemetery association shows just how instrumental the board was in the foundation of the cemetery’s earliest beginnings.

Issues include families moving out of the area and no longer taking care of the property. To this day, Bellefontaine Cemetery offers contracts outlining different types of perpetual care covering cleaning and landscaping.

One of the earliest amendments to the cemetery’s bylaws involved the regulation of plots once families were planning on relocating outside of St. Louis. This can be seen in the 1878 Bellefontaine Cemetery Association publication in which the types of shrubbery and plant life used are outlined.

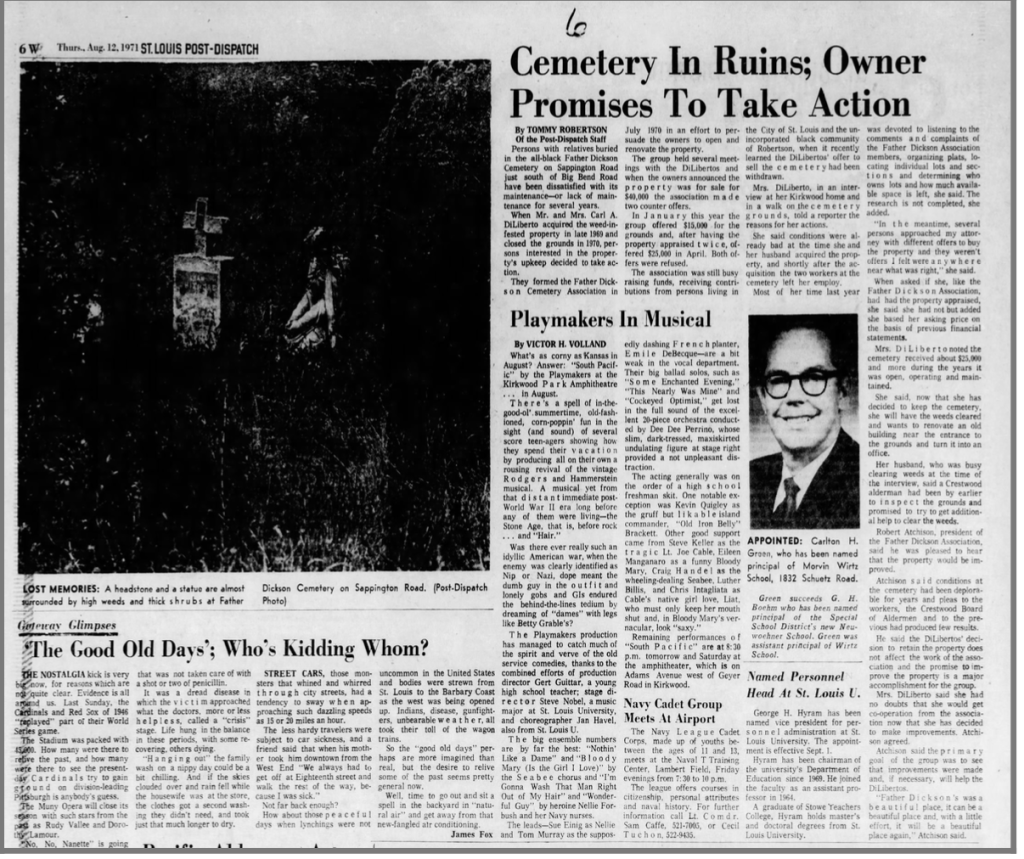

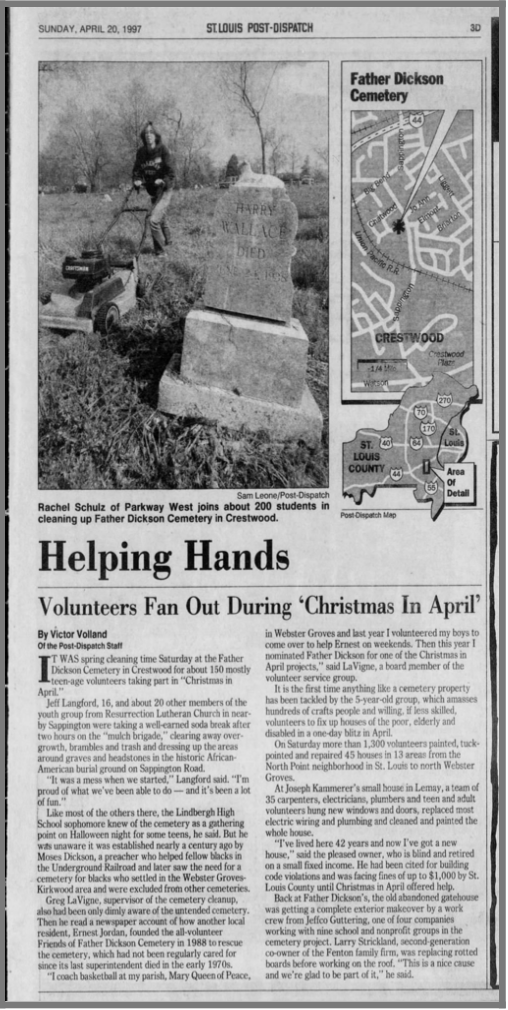

Father Dickson Cemetery was originally under the care of five shareholders. When the owners passed, the property was sold. Father Dickson Cemetery was sold multiple times throughout its history, and it would eventually become the property of the DiLiberto Family.

Father Dickson Cemetery did not have the same privileges as Bellefontaine. The original leadership structure did not consist of those voted in by lot owners and who had a personal investment in the cemetery as lot owners. As a result, there were no rules and regulations established surrounding the maintenance of the property. Additionally, there were no endowments to ensure the property would be well-kept. The result was that Father Dickson Cemetery would be heavily reliant on the surrounding community to volunteer to care for the property.

The long-term survival of a cemetery depends on more than geography—it hinges on the leadership models and preservation values embedded at its founding. When leadership is personally invested, and when structures like endowments and public elections are in place, cemeteries can adapt to change rather than disappear beneath it.