Too often, “progress” is used as a convenient excuse to displace the dead—especially when there are no living advocates to speak on their behalf. But what happens when the living do protest?

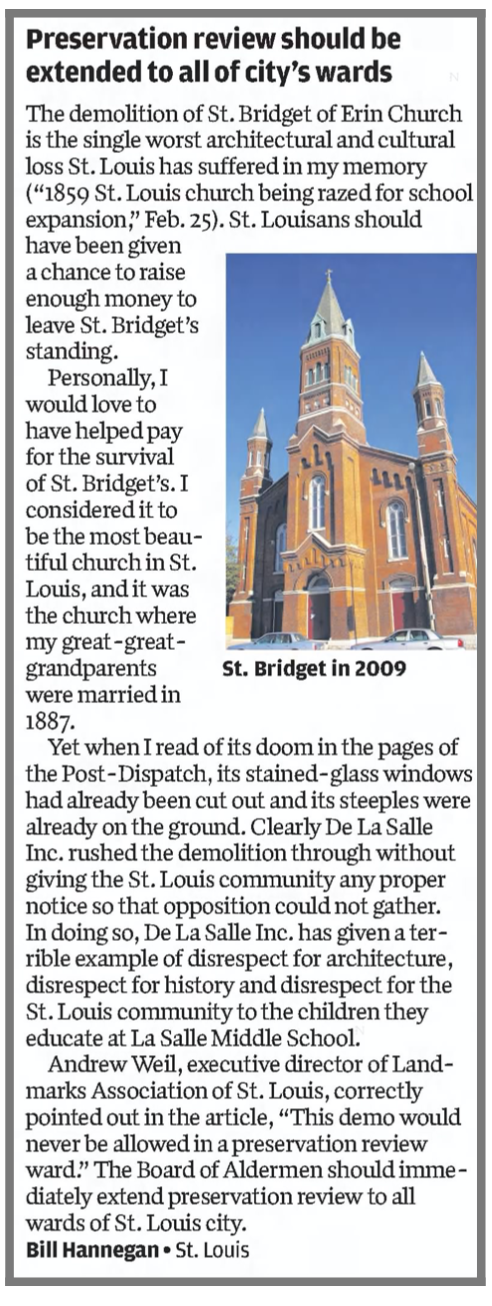

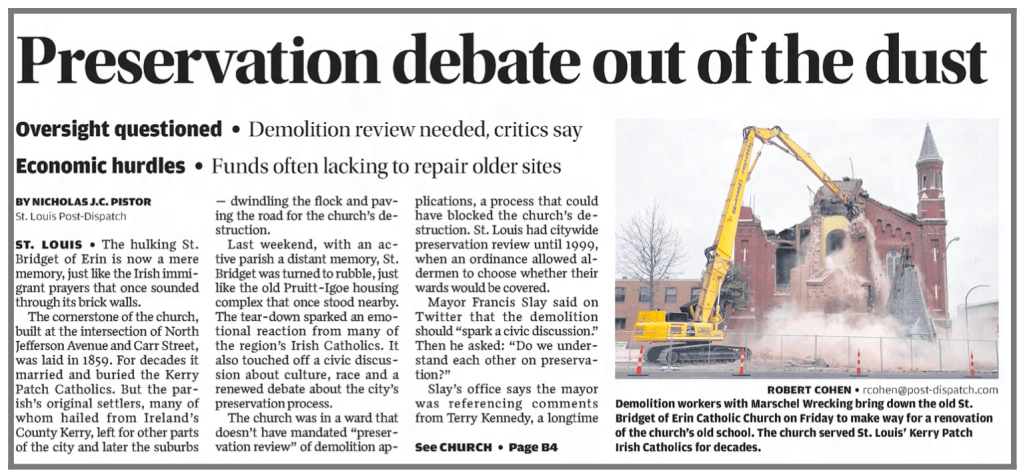

Take St. Bridget of Erin, a church that served as the heart of the Kerry Patch neighborhood for over 157 years. In 2016, it was demolished without any meaningful community input. Many residents only learned about its fate once the wrecking crews were already at work. The reason? The church stood in a ward without a preservation review board.

St. Bridget of Erin was not in an area that had a preservation review board. City-wide preservation review was the staple in St. Louis until 1999, “when an ordinance allowed aldermen to choose whether their wards would be covered.”

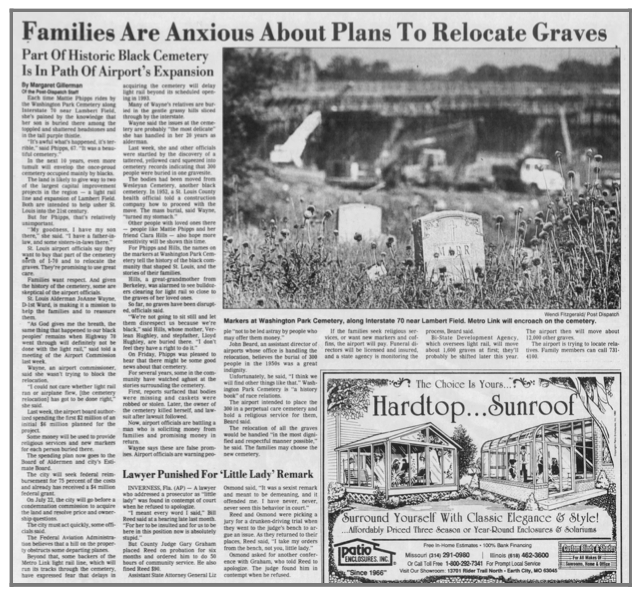

Four different construction projects; expansions of highway 70, Lambert airport, and MetroLink chipped away at Washington Park Cemetery. The result was the misplacement of many African American remains that, to this day, their whereabouts are unknown.

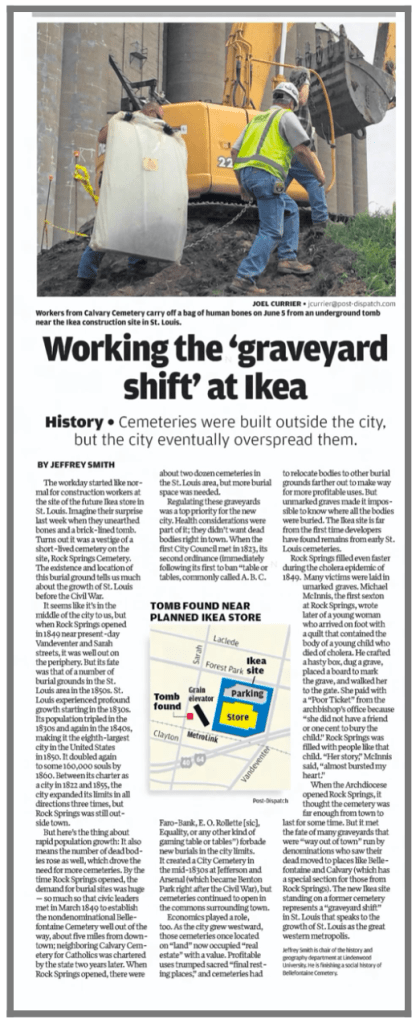

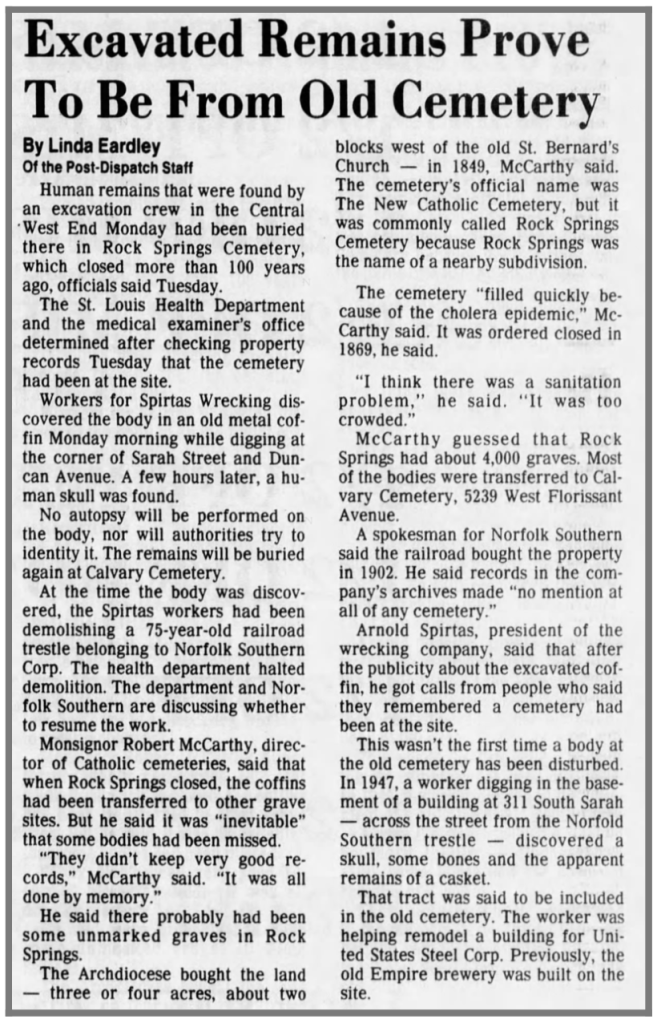

When Ikea was built over what was once Rock Springs Cemetery, the mayor refused to accept free help from a forensic anthropologist who wanted to locate and ultimately relocate human remains.

The motivation behind these situations is that the very existence of these historic sites hindered progress for the living. How accurate is that? When Rock Springs and Second Catholic were relocated, it is easy to see how they were moved to help St. Louis as a city grew, battled epidemics, and faced growing environmental concerns. City limits have been established for years now, so who benefits from the expansion of Highway 70, Ikea, and a vacant lot?