Death is a change of residence, so to speak. We move from one world to the next. The word cemetery comes from the Greek word koiman meaning “to put to sleep”. Often in American culture, we refer to cemeteries as “cities of the dead.” The way we speak of cemeteries in these two situations shows how we think of the dead as still existing in a similar place to us but elsewhere. Many family plots were designed to look like homes during the American Rural Cemetery movement. Some even have front steps and potted plants, as can be seen in the below photograph from Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. This style became too much to maintain long-term, giving way to the Lawn Cemetery Movement, and now many Americans find themselves seeking alternatives such as green burial.

Sometimes, memorials are outside of the cemetery. In some cases, the type of death determines the kind of memorial. For instance, car accident victims in both Greek and American cultures tend to receive a roadside shrine in addition to a more traditional burial.

One similarity in ritual with roadside shrines or Kandylakia in Greek is paying tribute to car crash victims by leaving temporary monuments on the side of the road near their location. It is important to note that in Greek culture, Kandylakia can be a monument to a dead person, but it can also be a monument to a close call with death. In American culture, the roadside shrines tend to be focused singularly on victims and not on brushes with death. Regardless of this distinction, in both cases, a space near the accident is dedicated as a spot to pay tribute.

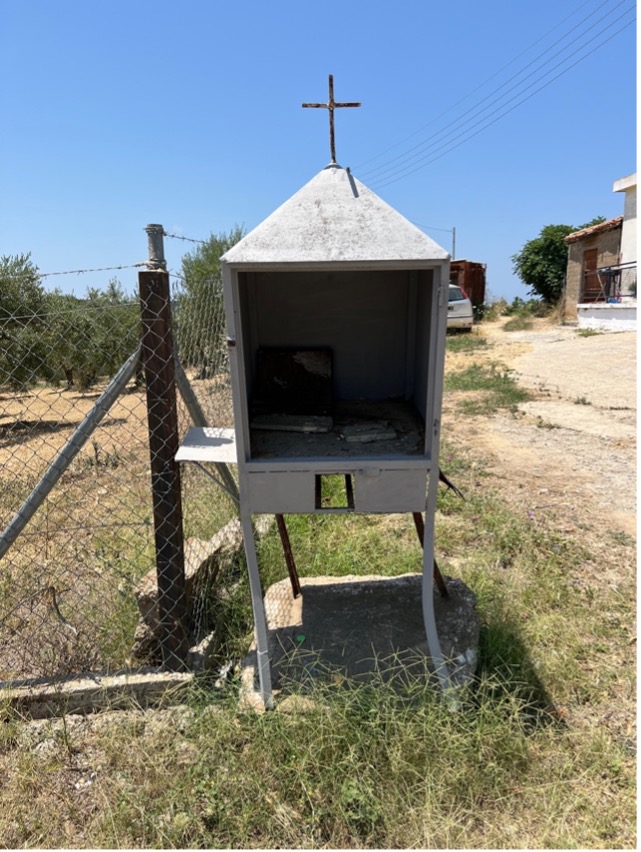

In the case of Kandylakia, they tend to be church-shaped boxes with a glass front for memorabilia to be placed and viewed. In American culture, a white cross is set up, and flowers with stuffed animals or photographs will be placed near it. Sometimes in the case of accidents that involve bicyclists, a bike will be set up instead of a cross. The bike will be painted white as well. This is referred to as a ghost bike. These ghost bikes can also be put up when a bicyclist was injured and not killed.

Despite differences in structure, the presentation is not that different. It is easy to think that black is the go-to color for death, and white is a symbol of things like innocence and purity and is used most often in weddings. However, black is a color symbolizing mourning and is worn by the living. At the same time, white is the color of the dead. Therefore the white ghost bikes or crosses are not so odd.

Another similarity is the religious iconography of crosses and churches. The items placed at the shrines can also be similar, with Greek culture leaning more towards religious iconography and American culture venturing into things such as stuffed animals and toys slightly more.

Additionally, how these monuments are allowed to decay over time speaks to the shared belief that life fades away and also moves on. All things die and decay, and monuments are no different. When flowers wilt and shrines are worn away, oftentimes, a solitary item remains, the cross or bike and the church-like structure. This is incredibly symbolic and can be seen in the photograph below.

The inside of the above Kandylakia can be seen on the right. The entire monument has been allowed to fall apart. This particular monument is only a few feet from a home. However, it is not the homeowner’s responsibility to keep up this monument. It is the responsibility of the community and those who put the memorial up in the first place.